blog

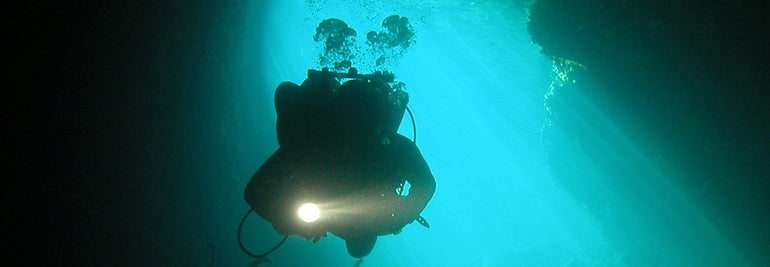

“Losing diving is like losing a limb”: Gemma Smith’s scrape with death and her incredible recovery

© Jukka Saarikorpi

Surgeons and specialists who’ve carried out 12 operations and other procedures on 27-year-old Gemma Smith since a car crashed into her have been astonished at how quickly she has recovered. Smith believes it’s in large part due to the massive kindness and support she has received from the diving community.

Fellow divers, for example, created a fundraising page for Smith to help her with her long recovery. At the time of writing they have raised nearly $10,000 USD.

Click here to support Gemma.

“The biggest thing I want to say to everyone is thank you,” says Smith, the first woman to dive the world famous Antikythera Shipwreck. “The support I have received from all over the world, from many people I’ve never met, has been so mind blowing. It’s beyond what I could have ever imagined.”

© Nina Baxa

When an elderly man died of an aneurysm at the wheel while driving in the Faroe Islands in March this year, his foot slipped on to the accelerator and the car veered off the road and into Smith and her friend as they were walking home from the shops for a movie night together. Thrown four meters by the impact, Smith, lucky to have survived, woke up in hospital, completely unaware of what had happened.

She suffered a bleed on the brain, a broken neck, a broken coccyx, both legs and both feet broken. With two e coli infections, Smith nearly lost a leg. Doctors doubted she would walk again, let alone don scuba gear and drop underwater.

But Smith is walking again, going to rehabilitation twice a week, and training to fulfill physical requirements set by doctors before they will allow her to dive again. Her determination is unshakeable.

Listen to Gemma talk about why she dives in the video below

Smith started diving when she was 17. Since then, this is the longest she has gone without a dive, and it hasn’t been easy accepting that.

“Not being able to dive is like losing a limb,” she says. “It’s not just that I’m missing my hobby, but part of me is missing. I'm really lucky, and I will never forget how lucky I am, but at the end of the day, my overriding goal and aim is to get back in the water.”

The harrowing experience, the loss of her ability to dive, the outpouring of support she has received from the dive community, has shifted Smith’s vision of her future as a diver. Diving will always be her life, but now she wants to focus on sharing diving with people who could really benefit from its healing qualities.

“When something this random and out of the blue happens, you definitely reassess what’s important and what’s not,” Smith says. “Whereas before the accident diving was driven solely by exploration and discovery, what I wanted when I was lying in hospital for weeks was simply to get into a swimming pool and just have that quiet. “I learned to appreciate that more than I had done before.

“My focus right now is to look at how to help people with PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) or who have been in horrible accidents, or had horrible experiences, through diving. I want to give people the opportunity to experience the wonder, freedom and calming influence that diving can bring to your life.”

Over the next year Smith’s plan is to get dive fit. First it will be a single tank dive in a pool. Then baby steps from there. And despite a warning from a neurosurgeon not to start anything new, Smith couldn’t resist beginning a degree in archeology. “I thought, ‘if I can't dive, this is not the end for me, I'm going to come at it from an archeological point of view’,” she says.

Everyone at Suunto wishes Gemma a speedy recovery and a wonderful first dive.

Lead images: © Jukka Saarikorpi

Drop below the surface into the depths with William Trubridge

Ask any freediver to explain what the experience of freediving is like and they will tell you words cannot do it justice. It's a transcendent sport – one that transforms our experience of the mind and our limits – and the subtlety of poetry is better suited to communicate what this unique experience is like.

“There’s nothing happening in your body that resembles any other sport or activity,” Suunto ambassador William Trubridge says in the video below. “What you are doing is perhaps the most alien thing the human body can do. Sure, if you went on a space walk, you are off the planet and weightless, but a free dive transforms you into another creature altogether.”

In the TEDx Talk below, Trubridge, who holds the world record for the deepest dive, guides his audience on a free dive, riffing poetically about the experience, how it feels, what happens to body and mind, and why he and other free divers are drawn away from the surface and into the deep.

Lead images: © Alex St Jean / Vertical Blue

Read more about freediving here:

How deep can we go?

You haven't understood free diving until you've read this.

William Trubridge talks record attempts and the art of freediving.

Under thin ice: Jill Heinerth captures climate change

Part of being an explorer is being away from home for long stretches. “Some people say that the two greatest times in the life of an explorer are leaving home and coming home,” Suunto ambassador Jill Heinerth says. “We will each feel loneliness and perhaps regret about moments away from those we love.”

“We feel an overwhelming imperative to document and share,” Jill Heinerth says.

But there are important reasons, sometimes for the greater good, that compel Heinerth and her peers to explore the ends, and depths of the planet. “We feel an overwhelming imperative to document and share,” she says. “When we have a chance to do really good work, telling important stories for humanity, then we are at the top of our game. Adventure fuels our souls.”

Telling an important story for humanity is behind Heinerth recently spending months in Greenland and the Canadian north. She has been on three expeditions to the Arctic to capture footage for an upcoming documentary film about the effects of climate change, called Under Thin Ice. She says the loss of sea ice is changing everything.

“The Arctic is warming faster than any other place on earth, so the changes are quite remarkable, even from year to year,” Heinerth says. “We learn from indigenous people that there are many new things they must adapt to. The sea ice disappears earlier each year. The multi-year ice is lessening and the migrations of fish and mammals are changing with the warming temperatures.

“Atlantic cod move further north into the territory of Arctic cod, competing for food. Bowhead and humpback whales are now seen in the same place at the same time. They used to arrive at different times, spread out by a couple of weeks. If everyone arrives at the buffet at the same time will they wipe out the food stocks? We know for sure that everything is changing.”

The sea ice disappears earlier each year.

Human-caused climate change is also impacting dive conditions, making it more challenging for Heinerth to do her job. “The bay in Ilulissat was filled with smaller bergs than normal, but it was choked with rapidly melting ice,” she says. “The freshwater mixes with seawater, creating a halocline that is difficult to focus through.”

“The melting ice also fizzes, filling the water with tiny bubbles. At times, we were in magically beautiful ice environments that were difficult to film. Warmer ocean temperatures also spawn more green algae that affects visibility.”

"It can take weeks or months of waiting to get the single opportunity for a great shot.”

“Any time you film marine mammals, there is a challenge of first finding them and then finding good and safe conditions for filming them. It can take weeks or months of waiting to get the single opportunity for a great shot.”

Heinerth, however, encountered more than enough wildlife for the documentary. On one day she got particularly lucky. Here is a passage from her journal on lucky day seven of her expedition to Nunavut, Canada’s northernmost territory:

Yesterday’s impossibly dangerous mess of jumbled ice is today’s floe edge, where ice meets the ocean. We are able to walk right to the margin and peer down into the black water. It is alive with narwhals and belugas. I spot a rare bowhead whale and we run for the cameras to try to capture the sight. The sounds are intense. Deep breathing and forced exhalations fill the air with moist spouts from dozens of blowholes. I can see narwhal intermingling with belugas and can hear the canary chirps of the white whales. Groups of seven or eight are huddled together on the surface talking and breathing up to prepare for a dive under the ice which appears to be about four to six feet thick.

Follow Jill Heinerth’s adventures on IntoThePlanet.com. And visit the official Facebook page for more information about the documentary Under Thin Ice.

GET BEHIND THE SCENES OF FILMING "UNDER THIN ICE"

Ocean plastics are a problem and no one knows better than divers

For anyone who spends a serious amount of time either working or playing in the ocean, it’s a near-impossible problem to ignore: plastics are filling our oceans. Even if your particular stretch of sand and water still appears pristine, it likely isn’t – as these materials (slowly) break down, they become microplastics – an ever more difficult problem to understand and deal with. In Long Island, the Bahamas, home to world-champion freediver William Trubridge and world-class freedive location Dean’s Blue Hole, it’s an everyday problem. We talked to the man who lives quite literally in the ocean what he is doing about it.

This is an issue you care about.

I have to – it’s in my backyard. Worldwide, plastic pollution – we reached the tipping point a long time ago. The Queen of England has banned single-use plastics from the castle! I’m an ambassador for the Ocean Conservation Alliance, run by Doug Woodring, who was one of the original people to discover and explore the Pacific Garbage Patch. His organization has done a lot for our oceans with things like their Plastic Disclosure Project – where they help businesses track their plastic use and offset it, much like companies do with the carbon footprint.

What does the ocean plastic problem mean for you?

Locally here – especially on my island – Long Island – the swell and tradewinds push garbage all to the north end of the island and it all collects in the bays and coves. And Dean’s Blue Hole is one of them. So we organize cleanups during events and competition, and we keep a bucket and just chuck in a little bit each day.

Where is the garbage coming from?

There’s a lot of theories about how plastic is getting in the water, and I think a lot of them are misguided. A lot of people blame cruise ships, but that’s not the case – you can see it in the trash itself.

More than half of the plastics that wash up in the beaches in the Bahamas are these little plastic bags of drinking water – in poorer countries, they get most of their drinking water from little 250 ml bags. They just tear off a corner and chuck it in the rubbish – but the rubbish ends up in the sea. And we’re downstream from them.

A huge amount of the plastic waste is those plastic bags. There’s also Petrol cans, cheap fishing nets. We’ll grab 20 or 30 toothbrushes in a day – the kind sold in Haiti or the Dominican Republic. They don’t have the infrastructure for waste management. Words are in French or Spanish. For us, there’s no question where it’s coming from!

And not only does the trash pollute, it doesn’t degrade, it just turns into smaller pieces – microplastics. For every plastic bag we see, there are thousands of millions of smaller particles you can’t see. Those all enter the food chain. So sea life is basically eating plastic all the time. And we’re at the top of that food chain. That can’t be good. Huge quantities of toxins are in the fish that we eat, and it’s killing sea life as well.

How can divers help?

The most effective way for divers is to help is to reduce their own use – less single-use plastic. Straws. Bring your own bags to the supermarket. Awareness of that is becoming more common – A lot of regions - cities, countries, are banning plastic bags. There is a ground shift movement to less plastic.

That’s in the developed world. But we also need to see that in the less developed world, and it’s a lot more difficult there. When you’re visiting those kinds of countries, put pressure on the local businesses, to take a more thoughtful approach to recycling and use.

And talk about it. Because most people simply don’t know. If you go into a supermarket in Honduras, talk about it. The more people that bring that message, the better. It will have an effect.

Doing cleanups and tackling that end of the problem helps, but not as much going to the source. Changing your own behavior and leading by example.

You also have some pretty crazy ideas about how to help.

One of the things I wanted to do, and so far it’s been a failure: I’d love to get the Bahamas to convert plastic to diesel. We have to ship in every once of diesel in the islands. There are machines – they’re not cheap – but you chuck in plastic and outcomes diesel. But in the end it’s quite effective if you have a good central hub. That’s a profitable way of cleaning up, but the initial investment is quite high.

You’ve also gone out on a limb about the plastic water bags.

Yeah – you know, some beaches are just carpeted with these bags. There are machines that obviously create this bag. The business that makes these machines in American, and basically aware of the fact that they’re creating a huge amount of waste that can’t be managed. So I got the CEO on the phone. Initially he was evasive, but he admitted that particular product that they are supplying is doing a huge amount of damage. His argument was that it’s better than bodies on the streets – people dying from clean water.

It’s hard to argue this defense – because it’s not completely wrong. So I’ve got in touch with a bunch of companies that work with biodegradable materials. Of course, any material that is biodegradable will biodegrade with water. So what’s left? The only other way is to change the whole system. In the Bahamas we use 5-gallon plastic jugs for drinking. But in a lot of those countries they can’t even afford to buy one or two jugs because they’re living so hand to mouth that they won’t even buy a jug. We need a few million jugs, and we get the government to ban plastic bags. Not as simple as it sounds, but we’ve got to get there somehow.

Learn more about the problems facing our ocean at Will’s efforts at the Ocean Recovery Alliance – and please, do what you can to help battle the problem!

Main image © Daan Verhoeven / Vertical Blue

Winning awards and making movies: just another year in the life of Jill Heinerth

If Jill Heinerth didn’t spend so much time underwater, we’d be a little more comfortable making this statement: the Canadian-American explorer is so darn busy, she barely has time to breathe. Between her expeditions, documentary filming, and you know, winning lifetime achievement awards, it’s a little tough to find a free moment – but unsurprisingly for those who know her, Jill was happy to fill us in. (And don’t worry – she’s got plenty of time to breathe.)

First, the awards. What did you win?

At the TekDiveUSA biennial conference, I was surprised with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the technical diving industry. In a fun tradition, they run a cave diving line into the audience to surprise the recipient. I was then blindfolded and had to follow the safety line to the stage while a show about my life was playing for the crowd.

It came with a trophy… and quite the compliment.

The award was a perfect little action figure of me in my diving and camera gear that was made by an artist in Poland. The citation read, “For a lifetime of consistent contribution and discovery that has opened up the field of technical diving.” But what really humbled me was that I was described as "our generation's Cousteau."

I still feel quite speechless. I am the first woman to be recognized for the honor.

Congratulations! On to the future. Where are you going to be this summer?

Filming in the Arctic, filming with French-Canadian filmmaker Mario Cyr. We’re working on a film documenting climate change, dramatic changes in the sea ice. We'll be working with local Inuit elders to hear about their observations and adaptations. We’ll be in Arctic Bay, Repulse Bay and Greenland.

You’re in a hurry.

The climate in the Arctic is changing twice as fast as anywhere else on earth. The sea ice sets up later and breaks up earlier each year. In fact, we had to move up our filming by a month due to the receding ice. Our climate change doc is being thwarted by climate change! Our Inuit hosts called us and recommended that we hurry north as soon as possible due to unprecedented break up this year.

So basically: ice is melting way to fast.

If we lose Arctic sea ice, we lose an important regulating function on global temperature. The white ice reflects the sun's rays back into the atmosphere. The darker open sea, absorbs heat, further increasing the feedback loop that rises ocean temperatures and ultimates affects the global circulation of water currents. Furthermore, both the people of the north and the wildlife rely on sea ice. The Inuit call the sea ice, "the land" since it represents their hunting ground and their ability to travel to other places. The wildlife also hunt on "the land.”

This is a big problem!

The entire food web of the Arctic relies on sea ice. From the algae beneath its surface that feed the zooplankton to the polar bears that roam in search of seals, all organisms use the ice as a part of sustaining their feeding activities.

To learn more about Jill’s Into the Arctic on the Edge film project, check out the website – and be sure to check out the teaser for her film below.

WATCH ARCTIC ON THE EDGE

What you absolutely, positively, must bring and do on your first dive holiday

Packing for vacation should be easy – a couple swimsuits, a pair of flip-flops, some sunscreen, and you’re good to go – right? Not if you’re going diving. To say it’s an equipment-intensive sport is putting it lightly. Good news: you can get your tanks at almost any dive location – so at least you won’t have to put down for overweight baggage fees. But there are a few key items you’re probably going to want. Suunto’s Alec Jones has spent the good part of a decade at the dive paradise of Sharm-El-Sheik as a dive instructor – so he’s a qualified expert.

First off, do a holiday

A dive holiday may sound extravagant, or expensive – but it’s one of the best ways to expand your horizons. “You’ll encounter different conditions, visibility, wildlife – you name it. Diving is about exploration!” says Alec.

Your own fins, mask and snorkel

Fins and masks are pressure points – you get the wrong fit, and you’re going to be uncomfortable all day, and that makes diving less than fun. At that point you might as well chuck in a snorkel. “Rental kit often isn’t so nice,” says Alec. “Even if you’re just getting into it, I really recommend getting a decent, properly fitting mask, and some decent fins.” And if you’re someone who would call themselves a germaphobe, you might, uh, want your own wetsuit, too.

Dry Bags, sunscreen and hydration

You’re probably going to be spending a lot – a lot – of time on a boat in the sun. Sunscreen you know about – but what you might not realize is how much you’ll get dehydrated. Add in that a lot of other counties purify their water – you won’t be getting minerals you’re used to – and it’s a recipe for dehydration. “A lot of people would come to dive in Egypt, get sick, and blame something in the water – but it’s actually dehydration!” says Jones.

Another great thing to bring along? Small or medium-sized dry bags to drag out on the boat – useful for electronics or just keeping a dry t-shirt nearby.

Gaffer tape and zip ties

Why? You don’t know yet. Just bring ‘em.

A dive computer you know

Your dive computer is an essential piece of kit – and since it’s a little complicated, it’s great to go with something you know. The new Suunto EON Core is an easy-to-use, Bluetooth®-equipped dive computer that will log every meter of every dive. With your own kit, you can pre-load it with your own dive plan – a nice bonus. Another hot tip? A portable power bank to keep your dive computer charged.

Keep going further

Water covers over 70% of our planet – there are lots of places to go. “For Europeans, the Red Sea is really close,” Jones says. “But why stop there? There’s Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, the Cenotes in Mexico, the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, the Galapagos – the list is really endless!”

Do everything right, and you’ll have the experience of a lifetime – and you might even make some new friends. “I’ve seen a lot of solo divers come down and make friends that they’ll keep for life,” says Alec. “Now they come back year after year to dive together.”

READ ALSO

A pro diver’s essential tips for newbie divers

10 tips to take amazing underwater photos

You haven’t understood free diving until you’ve read this

Freediving is not, as one might expect, a journey of meters or minutes – it’s the journey of a lifetime. While in the global scale of distance and time, a free diver’s trips to the relative shallowest depths of the oceans are small – the position one must put one’s self in to make such a dive requires immense dedication, patience, training and time.

Few can tell that journey better than world champion William Trubridge. In his new book, Oxygen, he invites us to join him for his life’s journey, and trust us when we tell you, what a journey it has been. To call his childhood ‘unorthodox’ would be putting lightly, or perhaps politely – born in England to world-wandering parents, he was traveling the world before he could walk. About that, in fact – he had to learn to walk twice. The first time on a boat – and the second time when the ground wasn’t moving beneath his feet. With his older brother and parents, they traversed the world, taking harbor in the Galapagos, the British Virgin Islands, South Pacific, and more. There were times where they wouldn’t see land for months at a time – including a 5500 km crossing to the Marquesas.

The obsession with the deep came early. Diving was a necessity of boat life. He recalls being impressed with their father, who dove 18 m to work on the boat’s anchor. When they met another boat family, led by a Frenchman named Benoît who could dive to a depth of 27 m, that depth seemed as deep as the sea would go. Little did William know he’d be trying for four times that depth a couple decades later.

Will sat down to write the book – for several hours a day, over many months after encouragement from friends and his agent Jason Chambers. He’s long-held fascination with the written word – something he delves into over the pages of his memoir – but the long format was something yet untried. One thing should be made clear: although you can learn a lot about the sport, it’s not a tutorial on free-diving.

“I tried to write it in a way that would explain the sport to those who haven't encountered freediving, giving a glimpse of how beautiful and peaceful it is,” says Will. “I also tried to include descriptions that might allow other freedivers to get a feel for my approach, the way I train, and why I've stuck with the sport.”

The meandering pages take you both through the days of Will’s life and the depths of his dives, digging into both the mindset he needs to be in to make them, the risks of being underwater, and how free diving happens mostly in your head. For someone who’s already gotten a taste of the deep, or someone who wants to, it’s a must-read.

Find Will’s book available as paperback or eBook on Amazon.com.

The freedive community raised $26,000 to help this hurricane-ravaged Caribbean island

To say Jonathan Sunnex’s life has taken a few unexpected turns is a bit of an understatement. How else would a Kiwi from Ngaruawahia, New Zealand come to be living on the little bay of Soufriere, in one of the least-known islands in the Lesser Antilles? But that question was hardly at the forefront of his mind while he sat at the airport in Miami – stranded thanks to a little storm called Hurricane Maria.

The entire Caribbean and much of the southeastern United States had a tense hurricane season – first Hurricane Irma barreled its way across multiple islands, then just five days later Hurricane Maria sprung up in its wake. While Dominica dodged a major hit with Irma, Maria was another story. The island suffered a direct hit – and almost three months later, much of Dominica still is without power or running water.

The fact that it was a pretty big wrench in the works of Sunnex’s biggest project of the year – the Blue Element Freedive competition – was essentially an afterthought. For Jonathan and girlfriend Sofia Gómez, it was a tense two-week wait in Miami, wondering if when they returned home they’d find their dive school – and their home – still standing.

“We were in Roatan for the World Championships,” says Sunnex. “We wanted to get back early to prep for Blue Element. It was scheduled for the 11th – 17th of October, but Maria hit at the end of September. It went from tropical storm to category 5 in just a few hours.”

At first he was hopeful the event could still go on – but as reports came in about the damage done to the island, expectations were quickly lowered. “We were really hoping our dive platform was still there,” he said. “Communication with people onsite was impossible.” But one of the first things he did? He set up a GoFundMe and reached out to the free dive community – hoping to raise a €1,000 of donations for food, water and other supplies. They ended up hitting their goal, and even bettering it – raising $26,000. The highlight moment? Jonathan – whose long, flowing hair had been growing for ten years – got on Facebook Live and shaved his head and cut off his beard, raising $700 in just twenty minutes.

With the bounty of the successful fundraiser ready to share with the island, he started making his way home – but it wasn’t a straight shot. “I flew to Martinique, and just started picking up supplies – water, chainsaws, literally thousands of dollars’ worth of food – whatever we thought we could fit on a boat,” says Johnny. “Then I hitched a ride with Piwi Croisieres Calypso over to Dominica.”

When he arrived on the island, he was ‘mostly speechless’. "The island is the greenest tropical forest – super dense bush – it looked more like a firestorm hit it,” he says. "No foliage. Bark ripped off of trees. No green left. It was a dry dusty desert. Piles of debris. Giant trees on the beaches, debris two meters high.” The damage to their home was real – the house/school was flooded, and the platform had been dislodged and blown to shore. They lost their competition rope, worth about $1500 – although it was later recovered, and they hope to repair it.

Without a doubt, the competition was off – so Sunnex and the competitors already on the island diverted their attention to clean-up and aid, cleaning beaches, roads and helping repair the island’s infrastructure.

There’s still much to be done – but Sunnex is confident the Blue Element freediving contest will return next year – and probably not during hurricane season. “The conditions here are impeccable,” he says. “Calm and flat, no current, water’s warm, perfect.”

Want to pitch in and help Dominica? See the Blue Element GoFundMe page here.

Want to take a great photo? Hold your breath

Diving was something I’d always done.

As a kid, while swimming, I spent more time beneath the surface than above it. But my free dive obsession really started with a SCUBA diving trip in Egypt. During that trip I actually was snorkeling with a friend, and trying to get our depth gauge as deep as we could. Which is a stupid thing to do, by the way. But I was having so much fun, I took a course in freediving… and haven’t been dry since.

My best was good enough for a Dutch National Record.

With fins to 60m, without to 55m, and free immersion to 65m. But I was a very average free diver during the time I was competing. At the time, 2011, the 55m was top 20. It’s nowhere near that anymore.

I’ve had seals kiss my camera

Last year, here in Cornwall, we were swimming with seals. Really shy in the beginning, but after a while, one was interested in my fins. Then he got close enough to my camera dome that his whiskers touched it. That was an interaction where you feel someone looking back at you.

I get in the water with a different mindset than the diver.

We both dive, but they have to go within themselves – all I do is look outside of myself. I look at them, the environment, the light. The same actions with completely opposite goals.

Safety dives helped me train.

At every comp, I did safety dives. There is a diver at depth and 30m. And because I did a lot of that, I knew I had a lot of stamina to do repeated dives. The deep guys go to 100m but do it once. The safety guys – and me – go to 30m, but we do it all day long.

I’m definitely, absolutely doing more work than the guys diving

I’m just not going as deep. I have to swim to 15m, see the diver, swim around him, get in front, crane your neck – and it’s a bad position. They’re going for maximum depth efficiency, I’m going for bursts of speed to get my shot. Totally inefficient as far as diving goes. I don’t become a better free diver by being a free dive photographer.

I love Will Trubridge

I met him first in 2007, but it took me till 2012 to work with him. Now we’re actually friends. He can be a bit shy. It took until I found out he had a wicked sense of humor for us to become friends. It’s nice to work with him – he’s a good delegator who tells you what he wants or expects, and he’s really clear about what he can do.

At Vertical Blue, I do fifty dives a day

Mostly hanging out between 10 – 20m. That’s my office, ten to twenty meters deep. That’s a depth where the light is still good, the background is good, and it’s easily achievable –I can do it on repeat all day long.

My dream dive is The Arch in the Blue Hole in Dahab

It’s an opening in a natural reef. The arch is at 58m, and then there’s a 30m overhang, then you have to go back up. To do the arch, with a camera, that would be spectacular.

All images © Daan Verhoeven / Vertical Blue

Read also 7 tips to help you make amazing diving videos and 10 tips to help you take amazing underwater photos

Learn more about Vertical Blue

WATCH THE WORLDS MOST AMAZING FREEDIVERS COMPETE TO WIN AT SUUNTO VERTICAL BLUE

In its 10th edition this year, the Vertical Blue competition is comprised of three depth disciplines: Constant Weight, Constant No-Fins and Free Immersion (CWT, CNF, FIM respectively). #VB2017 is an AIDA sanctioned event which offers competitors six official dives to challenge themselves to obtain the coveted title of “Champion” at the most elite freediving competition in the world.

William’s rival in free immersion, Miguel Lozano of Spain, will also be on hand to conquer new territory, as well as diving legends Davide Carrera & Homar Leuci of Italy. Heating things up for the ladies are world record holder Sayuri Kinoshita of Japan and first-time attendee (but renowned Italian mistress of the deep) Alessia Zecchini.

Over the course of the next 10 days freediving fans around the globe can watch the record-breaking battles among the world’s most talented athletes, who are literally pushing the limits on what was once thought impossible for the human body to do.

Stay tuned here and via the Suunto Diving + Vertical Blue Facebook pages, the VB event website, Suunto & VB Instagram, the VB Youtube Channel, Trubridge’s Twitter feed as well as the Vertical Blue twitter handle & hashtags #VB2017 and #verticalblue for a live feed from the platform, amazing videos & images and results.

Join us as we watch dive history in the making!

All images © Daan Verhoeven/Vertical Blue

The coolest dive partners aren’t humans – they’re sea lions!

There was easily a couple hundred sea lions around

The sea lion colony at Hornby Island is active, and has little fear of people. My dive happened to be right around the biggest herring spawn of the year, meaning they were all around waiting for a feast. Ones you see solo in the wild tend to be a lot more shy.

They just want to play…

Of course, sea lions can be dangerous. I’m not saying you should go out and hug a sea lion – but if you happen to dive with this group you don’t have a choice. As soon as you’re in the water, they just want something to play with. They can come across as quite aggressive – they’ll nip at your suit, the top of your head, or tug on your wings, but they aren’t trying to injure you. I’ve had one put his full mouth on my dorm port – and another one yanked me up to the surface to play.

… but it’s on their terms

When they’re done, they’ll just head back to the rocks to sunbathe.

These are ‘Stellar Sea Lions’

That’s actually the name of the breed. I saw a few California Sea Lions as well, but mostly Stellars.

It’s super obvious they’re super smart

When you dive with these sea lions, you get the perception that it’s all play. They’re very curious, and they’re very trainable. At the seaquarium, they train the sea lions to undergo all sorts of vetinerary procedures to keep them healthy.

That part of British Columbia is absolutely stunning

On this trip I was diving a wreck called Capilano. There’s so much to see underwater. Some of the best diving in the world! Nutrient rich water year round. Stunning wildlife. Plenty of wrecks.

We dove during a blizzard

Full white-out topside. Great visibility below. Sure, the water is cold, but the air above was even colder. If you’ve got the right gear it’s no big deal.

One sea lion loved my Suunto Eon!

He kept tugging at my dive computer – at one point he even looked like he was checking out my dive stats. So maybe one day they’ll make a good diver partner anyways!

Diving offers a unique chance for humans to observe marine animals in their native environment. Stay tuned for even more incredible stories of divers and the denizens of the deep sharing space beneath the surface of the sea!

See what a diving expert wants you to know about SCUBA

It’s not suppose to hurt your ears

When I was a kid I dreamed about diving, but my ears and sinuses screamed in pain – but when you take a Scuba class you learn to equalize naturally. Diving should never be painful. Your ears hurt because of the effects of pressure – the volume of air spaces within your body are compressed by water pressure over your head. You need to adjust that change with equalization.

You’re not breathing what you breath on land

Most people mistakenly assume there’s an oxygen tank on your back. You’re not breathing oxgygen, you’re breathing what you’d breath on land, and that's 21% percent oxygen, 79% nitrogen and a few trace gasses – but it’s dried, filtered clean, and compressed. Technical divers may use exotic gasses like helium to conduct dives at much deeper levels, but recreational divers just breath, well, normal air.

How long can I stay under water, really?

That’s a tough questions! There’s a lot of factors that limit your dive. Important ones being how much air is in your tank and how deep you go. Recreational divers generally can ascend to the surface at any time during their dive with no need for de-compression stops on the way.

Uhhh, what are decompression stops?

Technical divers have an artificial ‘ceiling’ over their heads (or sometimes a real one). Artificial ceilings are created when you go deep or very long, and your body needs to time climatize and release gasses that have accumulated in the body. If you go higher, faster, you could get injured – it’s called decompression sickness (colloquially known as 'the bends’) and trust me, you don’t want to deal with it – symptoms include joint pain, headaches, neurological damage, even paralysis. But let me be clear: this is totally, 100% avoidable.

How safe is diving?

Statistically, diving is incredibly safe if you’re following the rules and know what’s going on. You’re more likely to suffer a fatal bowling injury! But you need to follow the sea conditions and weather, and follow the basic safety rules you learned in dive class.

Will my whole body wrinkle up like my fingers after too long in the pool?

Ha! That’s great, but no. You won’t come out looking like a prune.

What’s a dive algorithm?

A dive algorithm is a complex mathematical formula that attempts to simulate how the human body deals with the inert gas in scuba diving on descent and during the dive. It predicts how the body will off-gas that same inert gas to allow us to find the proper schedule for a safe ascent back to the surface. See the above statement about ‘decompression stops’.

Give us a sample dive profile?

A ‘dive profile’ is basically a map of how deep you go when (and for how long) during a dive. A rec-diver going to 30m of depth has only of 20min of bottom time before they ascend back to the surface with no safety stops. Alternatively, tech divers will spends hours at 30m, using rebreathers and different gasses to complete that dive, and they’ll have a number of decompression stops to come back to the surface.

Are there any long-term effects?

The current algorithms keep us in the safe envelope of exposure. I’ve got 7,000 dives, and sometimes am on projects that extend for months, diving every single day. Researchers are still looking at us (by that I mean people like me!) to see if there’s any long term effects. Decompression stress – the same thing that astronauts deal with, just on lesser levels – is of great interest to physiologists – there’s a lot of questions about how that stress expresses itself on bones or tissue over very long periods of time. But I’m 52 years old, and can still swim circles around most 20 year olds, so I’m not too worried for the long run!

Stay tuned for more articles about the science of diving.

READ MORE

Explore a frozen world with Jill Heinerth

How deep can we go?

Watch these divers explore the Abaco Blue Holes –?live!

Even if you’re just a casual diver, you’ve heard of Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas. The deepest saltwater blue hole in the world, at over 200m, it’s a mecca for underwater adventures of any sort – from scuba divers to free divers.

But what many don’t realize is the island nation is home to not only this natural wonder, but many more as well. The caves are referred to as the Abaco Blue Holes, it’s one of the most diverse and vast cave diving areas in the world – with many caves still unmapped.

That’s precisely why Suunto diver Jill Heinerth will join an elite crew of divers in the Bahamas for a massive survey and documentation push on the Abaco Blue Holes.

"I will be joining an elite crew of some of the finest cave diving explorers on the planet, lead by Dr. Kenny Broad, we will be joining Brian Kakuk of Bahamas Underground, and the Friends of the Environment in Abaco,” says Jill.

The area is rich in dive history – her partners on the project have been exploring these caves for over two decades. You can make legendary dives through areas like Fangorn’s Forest in Dan’s Cave, or see artifacts such as 3,000-year-old crocodile skeletons in Sawmill Sink. Of course, diving here is with no small risk – as always with cave diving, the right equipment and a wealth of experience from at least someone on your team are absolute necessities.

What’s the occasion for the study? "After over a decade of hard work, these blue holes have recently become protected within a newly designated national preserve,” Jill tells us. What’s even more interesting is that while this project is an underground operation, it isn’t undercover. They’ll be broadcasting almost live. “The team also has an aggressive outreach initiative that will include satellite transmissions to classrooms from the field and advanced 3D imaging efforts that will help to develop interactive resources that will help topside visitors get a sense of the beauty that resides beneath their feet.”

Things they’ll see in the caves include stalactites and stalagmites formed by deposited calcium. They can be rich environments for marine life – Bahamas-based diver Brian Kakuk calls them ‘overstocked aquariums’ – and they hold unknown potential for research – and it’s big win for research. These caves have been important laboratories for climate change science and biological studies and their new added protection will undoubtedly offer many more opportunities for science.

Follow along to see the Abaco Blue Holes project in action!

Watch Jill Heinerth’s Expedition files on Youtube.

Get ready for hangouts by satellite: Virtual Field Trips to the Bahamas!

This week a new BGAN unit (textbook sized device that allows video Google Hangouts from pretty much anywhere on the planet) will head by boat to Abaco in the Bahamas on a National Geographic Expedition with Kenny Broad and Jill Heinerth.

The next hangout, an EBTSOYP Hangout, will be on December 8th @ 11am EST. Lots of camera spots available and you can check out a background hangout with Kenny and Jill here. >>Watch a replay of the Virtual Field Trip here<<

Read more about the project at intotheplanet.com

This is what the perfect dive trip looks like

Last month, we sent Suunto #DiveWithMe winners Anna Starup and Theresa Thorp to the Philippines for a little dive adventure in paradise at Atmosphere Dive Resort – suffice it to say the girls enjoyed themselves. Now that they are answering e-mails again (because let’s be honest, we wouldn’t be answering e-mails on a dive vacation either) we pinged them with a few questions about the trip – and of course, got some pics.

Anna, this was a learning experience for you.

Anna: Yeah – I did my final certification in the Philippines after preparing at home in Denmark using online courses. Diving just caught me right away. In retrospect I’ve thought about why I didn’t take my open water earlier. Diving is definitely going to take me (and Theresa) to places in the world I’d never considered before.

Best single dive of the trip?

Anna & Theresa: That’s actually quite a hard question! The dive sites differed a lot and each had amazing aspects about them. Perhaps a dive at Apo Island where we saw a dozen turtles that played around with us. Or a dive where a blue-ringed octopus saw its reflection in Anna’s dive instructor’s camera and attacked it! At the same dive we saw 4 species of Octopus’ and a lot of cool frogfishes.

Of course, you didn’t spend every moment on the boat…

Anna & Theresa: Atmosphere quite is a little piece of paradise. Rooms, dining area, dive shop, beach – just amazing. We’ll have to mention the food here as well. Besides diving, eating was definitely a highlight every day! The people at Atmosphere were a huge part of the amazing experience we had. Everyone seemed like a little family, joking around, stopping for a chat, taking interest in each other’s (and our) lives.

You made such good friends, you even got a nickname…

Anna & Theresa: Someone from the dive crew, jealous of our cool Suunto D4i, nicknamed us “The Suunto Girls”, which kind of stuck to us for the whole trip. Not the worst nickname, right? We also have to send a special “thanks” to Ulrika, Marco and Daniel from the Atmosphere family, who were the main reasons why this trip became such an irreplaceable and spectacular adventure. We’re still feeling completely and utterly high on life, thank you!

And you even got into the jungle!

Anna & Theresa: On our way to the resort we met up with Theresa's brother and friend who is currently backpacking their way around Asia. We woke up at 5AM for a short jungle hike which led us to the most stunningly beautiful, lagoon called Kawasan Falls. Being there early meant having the waterfall all to ourselves for hours! A ton of fun swimming, cliff jumping and playing around in the lagoon before we continued on our journey to Atmosphere Resort. We also got to explore the Chocolate Hills, joined a dinner cruise at Loboc River, saw the Tarsier Sanctuary at Bohol Island, and visited Osmena Peak, the highest peak at Cebu Island. All spectacular sights and irreplaceable small adventures.

Do you feel more confident underwater?

Theresa: Getting to share the incredible underwater world with Anna for the first time was magical! We had so much fun during her Open Water Course, and later during our fun dives.

Anna: I had studied quite a lot of theory, but all of it made sense when I got to try it in the water. I wasn’t sure how much I was going to remember if a situation occurred where I actually needed it, but during my very first dive for instance, my mouthpiece came off. Without knowing exactly what was going on, I just grabbed my reserve. So I think some of the exercises “internalizes” pretty fast.

Can you name some of your favorite spots for future visitors?

Anna & Theresa: The "turtle" divesite at Apo Island was called Rockpoint West. The divesite where we met the blue-ringed octopus was called Secret Garden although we called it Octopus' garden, as we saw a lot of octopus there. The whaleshark spot was called Oslob.

Are the Philippines as a must-go dive destination? Theresa: Absolutely – especially if you're into muck and micro diving. It caught me right away, and I'm still in awe that critters, like the one we met, actually exist in real life! I was especially fascinated by the many different species of frogfish, nudibranch and mantis shrimp.

Would you go back?

Theresa: Definitely! The amazing dive sites and spectacular nature are sure to drag us back, and besides, we need to reunite with the amazing crew at Atmosphere Resort.

What other spots in the world are next on your must-dive list?

Theresa: Since this was my first time diving in Asia, I'll have to get back to explore some more! Right now places like Komodo, the Gili islands and the Maldives is on the top of my must-dive list. Galapagos has also been on the top of my list for quite some time now.

Explore a frozen world with Jill Heinerth

If you dream of diving unique and undiscovered places – let’s say, under Arctic icebergs – there are very few people in the world who can tell you what it’s like. One of them is Jill Heinerth, one of the first people in the world to dive underneath an iceberg back in 2002. Here’s a few bits of wisdom about the world’s coldest, loneliest places passed on from one of the sport’s most knowledgeable individuals.

It’s one of most unique experiences you can have

Diving inside an iceberg in Antarctica was one of the most remarkable things I have ever seen underwater. There were no guidebooks to prepare me for those experiences. Nobody had done it before.

It’s nothing like cave diving

Iceberg diving is actually very different from cave diving. There are odd vertical currents and surging swells created by mixing waters and bouncing masses of ice heaved up and down on waves. Most iceberg diving is done along a face or wall of ice rather then inside a cave-like area. There are significant risks from going inside a crack or crevasse. Icebergs, especially in the north, are dived at the end of their lifespan. They are fragile. They roll, crack and move in a way than crush a diver in an instant.

Wanna dive an iceberg? Head to Iceberg Alley

The best place to dive icebergs would be to head to Iceberg Alley in Newfoundland, Canada and dive with operator Ocean Quest Adventures in the early summer months of June and July. They have experience guiding groups to safely dive the icebergs and when you get your fill, you can swim with whales, dive WWII shipwrecks and even dive in a flooded mine.

This isn’t for dive rookies

You’ll need to have proper exposure protection for the cold water and advanced diver training that includes excellent mastery of buoyancy control, comfort with shooting a DSMB, using a compass and drifting for a safety stop in open ocean. You also need to descend quickly without a reference line since the most dangerous place to be is near a face of ice on the surface of the water.

And you’re going to need a helmet

In case a loose piece of ice strikes your head. I have been swept through an iceberg on a rocketing current, been inside a cave when the doorway disappeared, was pinned to the sea floor by a raging flow of water and watched an entire iceberg explode into a sea of slush.

Speaking of risk, it’s cold – really cold

Cold water increases the risk for any dive profile. How long you can tolerate the chilling temperature? Cold water can affect your mobility and comfort if you are not well dressed. You also need to consider drysuit flooding and managing thermal profiles to avoid decompression stress and gear-related risks such as regulator free-flow. You also need to get back quick – a long float on the surface while you await a pickup isn’t an option.

We’ve all made plenty of mistakes in diving. If you haven’t made mistakes, you likely aren’t diving. I’m not embarrassed to report that I have made my share. The important thing is that you plan conservatively enough to absorb the issues and come home safely.

Icebergs scare me. Always. But my careful forays into the deep chill have been incredible experiences.

You’ll literally be swimming through history

There is no doubt that icebergs are stunning visual environments. You might be shoulder to shoulder with an ice wall formed by 10,000 years of compacted snowfall or be witnessing the fizz of earth’s atmosphere erupting from some ancient timeframe. Scientists certainly have a lot to learn about sea ice and declining ice shelves around the world and in my lifetime, it is predicted that we may have an ice-free Arctic. Is it worth the risk? I’ll leave that to adventurers and scientists to consider on their own.

You can come dive icebergs with me

I will be making The Journey of the Iceberg next fall. On Sept. 23, 2017 I will be departing on Adventure Canada’s boat to make a trip from Greenland, across the Davis Strait and down the Labrador Coast to Newfoundland. We have space for ten divers to come along on this amazing opportunity to dive in places never visited with SCUBA! Icebergs calve from the coast of Greenland and make this circular journey across the strait. We’ll follow their course and have incredible diving and exploration opportunities along the way.

READ MORE

SIGNAL SEEKER – A SHORT STORY ABOUT BO LENANDER'S LIFELONG JOURNEY

EXPLORING THE LITJÅGA CAVE

Exploring the Litj?ga cave

In this second part of the Arctic cave diving series, we will explore the Litjåga cave in the Nordland region of Norway.

A fierce wind blows over the open plateau. White Mountain tops in the horizon fade into the gray sky. There seem to be so many fells that I wonder if they all even have a name. The road carves a deep track into the snow. The wind is doing everything it can to fill in the track, to erase our narrow path from the landscape.

This spectacular landscape belongs to the Scandes, a mountain range that originated some 400 million years ago when Greenland crashed into Scandinavia. This violent collision created a huge mountain range, higher than the current Himalayas. Called the Caledonide Mountains (Caledonide being the Latin name for Scotland), the range reached from Scotland to islands of Svalbard. We actually see the remnants of the insides of these huge mountains. Erosion has worn them down, and many ice ages have carved the valleys. Inside these fells are huge deposits of limestone, formed by the calcite-rich sea floor that was pushed up by moving land masses into the mountains. During the process, the limestone turned into layers of marble, creating favorable circumstances for caves to form. Over the years, water has carved its way through the stone, creating water filled tunnels we shall soon be exploring.

As the night falls, we descend from the plateau and enter the thick forest of Arctic spruce. The familiar landscape of the Plura valley greets us. Our car slowly makes its way along the icy road, sliding at every tight turn of the narrow road. We cross the Plura River that originates in close-by Kallvatnet, a vast reservoir 564 meters above sea level. We take the road running along the valley. The last house in line is our target. It is Jordbru, the Traelnes family farm.

We are staying next to the spectacular Plura cave, but this time, it’s not what we are here for. Our goal is to explore Litjåga, trying to find out the secrets of the unexplored part of the cave. In this region of Rana, just south of the Arctic Circle, there are about 200 known caves. Altogether about 2 000 caves have been listed in the whole of Norway. Most of them are unsuitable for diving, either because they are dry, too small or too remote.

Compared to the tunnels of the Plura cave, Litjåga is lower and narrower, but it can still be dived with back-mounted equipment. Norwegian explorations before us have taken the line to the third sump, a total distance of about 1.4 kilometers from the entrance. That is where our lead divers Sami Paakkarinen and Kai Känkänen intend to continue further on.

Day 1

The dawn is gray. Fell tops line the horizon. The wind makes its way up the valley; reminding is what it can be like when the weather gets bad. It is often much colder at this time of the year; luckily the temperature is closer to zero degrees Celsius. Although the water temperature is always the same, surface operations are much more demanding in bitter coldness, freezing the diving equipment and cameras.

We assemble our gear and make the last adjustments. We shall be spending over ten hours inside the cave. It means that we need to pack food, clothes, and lights in dry tubes. The tubes need to be carefully balanced to be neutrally buoyant. Dragging tubes along the cave floor or ceiling is not an option.

Finally, the cars are packed, and we are on our way. Litjåga is along Route 6, a highway from Mo I Rana to Bodø, south of the spectacular Saltfjellet-Svartisen National Park. The highway is like a downhill skating track, as the snow covering it has melted during the previous day and frozen again overnight.

Snowmobiles are the means to transport the gear to the Litjåga spring during the wintertime. The snow plays its usual tricks when Sami and Veli are hauling the heavy sled over the white banks.

Torsten Traelnes, the owner of the Plura farm, has kindly loaned us his snowmobile. It has been packed onto the back of his old pickup and hauled on-site, ready for action. With the snowmobile, we can transport the gear over the last half a kilometer of waist-deep snow from the highway to the cave entrance. Although the temperature is quite high considering the time of year, the winds up in the fell make the air biting cold.

The Litjåga spring water levels are down, so we are met by a tranquil headpool. There is a constant flow of water supplying a serpentine creek. It takes us a couple of hours to lower scooters, cylinders and rebreathers down from the steep snowy banks of the spring.

Sami inspects the tanks, rebreathers, dry tubes, scooters and cameras before the dive.

We have brought plenty of cameras to document the event. Thomas Broumand is operating a buzzing quadcopter over our heads as we put on our gear. It sounds like a swarm of mosquitos, reminding us of the summertime. It takes a while to get used to the copter and not stare at it all the time. Janne is carrying the underwater camera, and everybody else is equipped with a video light.

The Litjåga spring water levels are down, so we are met by a tranquil headpool. The exploration begins here.Our plan is simple. We have three diving days for the project. The first dive is dedicated to taking tanks and dry tubes through sump one and carrying them over the dry section to sump two. Litjåga is a relatively shallow cave, its depth never exceeding 22 meters. This makes things easy for us, as we don’t have to take deep range gasses into the cave. Also, the volume of bailout gas is quite small. Going deep means an exponential growth in the required open-circuit volume, not just in the number of required gas mixes.

Veli Elomaa and Jenni Westerlund descend first into the crystal clear waters, disappearing into the stony well leading down and underneath the fell. Janneand Ifollow, making our way through the narrow passage at the beginning of the cave. We are only just barely able to drag ourselves through the restrictions with our JJ rebreathers. The layered stone forms sharp ledges sticking out of the ceiling and floor. As a result, Janne’s suit springs a leak, making him instantly cold. Fortunately, we are only planning to take the equipment to sump one today. Otherwise, we would have to turn around and fix the leak before continuing. We wait for Kai and Sami to follow, to get some good footage of them pressing through the narrow part.

Time to go. It will be another 12 hours before we will see the headpool again.

After the restrictions, the cave opens a bit. The video lights reveal a colorful cave, formed of various shapes of limestone. The maximum depth of sump one is 22 meters and the length of the sump is close to 500 meters. The low ceiling requires careful scootering, especially while dragging the meter-long dry tubes behind us. The cave soon plays another trick on us. Sami’s scooter catches on some rubble. One of the propeller blades snaps. Luckily this is the set-up dive with plenty of time and a short distance, so we simply carry on without the scooter and bring it back to the surface later for repairs.

The first sump contains a few restrictions and eye-catching marble formations. The layered stone forms sharp ledges sticking out of the ceiling and floor. The maximum depth of sump one is 22 meters and the length of the sump is close to 500 meters. The low ceiling requires careful scootering, especially while dragging the meter-long dry tubes behind us.Surfacing in the dry chamber gives us an immediate idea of the coming challenges. The passage is so low that dragging the rebreather through will mean crawling along the bottom, faces in the silty water. We leave the rebreathers waiting and slip the bailout cylinders through the restriction. After some crawling we enter a 250 meter long dry section has been washed clean by the rushing waters, leaving behind a polished floor of marble and intermittent sand banks. Parts of the dry cave require crawling or kneeling down, which make the 40-kilo dry tube less friendly than in the water.

The team surfacing in the first air chamber. From here begins the heavy carrying of gear to sump two, with over 250 meters of crawling and wading.

Although we are taking only some dry tubes and stages through the dry section, one of the key challenges of Litjåga is apparent. While working in our dry suits, we soon start to sweat. Our thick undergarments are making things worse. When returning to the cold water, I can immediately feel the problem. Diving in four-degree water while being wet is not the most pleasant of feelings. We use heated vests to keep the upper torso warm, but it does not fully compensate the heat loss caused by the wet clothing.

We surface after three hours underground. We have taken the heavy stuff in, helping us move quickly and lightly on the push dive. It is time for some rest at the farm.

Day 2

The goal of our project is to extend the line laid inside the cave and to do detailed documentation of the cave. For the purpose, we are using the traditional means of measuring the laid line and directions, but also brand new technology. Sami is carrying an underwater tablet containing software for making precise measurements under water. We also have many GoPros and other cameras not just for stills and video, but also for taking footage for photogrammetry. This new technology allows us to render a computer-aided 3D model of the cave based on video footage and a few measurements. All these gadgets don’t always make things easier. We are delayed because the remote location in the Plura valley obstructs the cellular connection required to update the tablet’s measurement software, something that we had forgotten to do beforehand.

Kai and Sami discuss the exploration plan at the Litjåga spring.

Kai and Sami are the designated push divers. The plan is to dive quickly through sumps one and two with the whole team and carry the equipment to the beginning of sump three. Kai and Sami go first so that they will have enough recovery time before doing the push dive in sump three. We follow a few minutes later.

The dive goes smoothly and everything works fine. We soon surface at the other end of the sump. The first task is to crawl through the restriction, face in the water and rebreather on your back, trying to find a big enough space to squeeze through. Everybody’s panting heavily and cursing as their elbows and knees hit the rocks. I try to shield somehow my dry suit made of Kevlar. Getting a hole in the suit at this point would mean that I had to turn back. It takes about an hour to carry the gear over the dry section and get ready for the second leg.

In sump two the passage gets narrower. The buoyancy of the dry tubes seems suboptimal, causing silt to stir up from the bottom. The visibility gets low, and we stick to the line closely.

After sump one, we enter a 250 meter long dry section has been washed clean by the rushing waters, leaving behind a polished floor of marble and intermittent sand banks. Parts of the dry cave require crawling or kneeling down, which make the 40-kilo dry tube less friendly than in the water.We surface and meet the lead divers in the dry section between sumps two and three as planned. They are already scouting routes for carrying the equipment to sump three. The dry section after sump one was reasonably easy regarding carrying, with plenty of headroom and a relatively flat bottom. Only in the beginning and the end of the dry cave did the ceiling force us to crawl or kneel. This second dry passage is a totally different story. Its steep walls and narrow passages force us to move slowly and carefully along through the 350 meters of the dry cave.

There are two routes to choose from. The lower route means either wet feet or sweating in the drysuit. The upper route leads over treacherous leaps, with 3-4 meters to the stony floor. Carrying a single stage feels heavy, and there are many trips to be made before the gear will be ready for the push dive in sump three. The stones look solid, but they are not. Crossing one of the chasms, a layer of rock suddenly comes loose under my grip. Swaying forcefully to my side I hit the wall, watching the big flat stone hit the floor with a thundering crash. Hanging on to the rock I realize that having a broken leg this far inside would not be a good idea. Getting out through all the restrictions would be a dangerous undertaking while seriously injured.

Lunch time. Some warm food to warm up the team.

Eventually, we have everything carried over to sump three. It is lunch time. Veli has brought a gas burner that we heartily welcome. Hot soup and meals made from dried ingredients feel incredibly good as the moist, cold and work has started taking its physical and mental toll. Soon Sami and Kai are ready for the push dive. Standing on the narrow strip of sand, we help them kit up and wish them good luck as they disappear into the darkness. We have no idea how long we will have to wait. It all depends on how long the diveable cave continues. We return to the campsite. There is nothing to be done but wait.

After some 90 minutes, we are heading back to the sump three from the camp site when we hear noises. Kai and Sami are up. It either means that they have not made it very far from the end-of-line, or they have had some problems. As it soon turns out, they have laid new line but had soon run into an impenetrable passage.

In the end-of-line, the cave continues along two different routes, both impossible for rebreather divers to pass. The lower passage ends in a narrow passage, accompanied by a shifting gravel slope. Going through it would mean digging oneself headfirst into a pile of gravel at a depth of 70 meters. Being upside down in a shifting wall of sand is not very tempting option. The upper passage is so narrow that there is no way getting through it in back-mounted gear.

Kai and Sami had no option but to turn the dive around. They were only able to lay 40 meters of new line, increasing the sump 3 line to a length of just over 200 meters, and to almost 1.5 kilometers in total. In a sense, the dive was a success as it was carried out as far as possible. It was an obvious disappointment that there wasn’t more cave passage to follow.

Sami getting his measurement and mapping tools ready.

Could the line be continued one day? Maybe with side-mounted gear and some serious tools to deal with the restriction. But as the cave was already getting so much narrower, the chances are that the diveable passage wouldn’t continue very far. Time will tell whether this really will remain the end of the line. In any case, the challenge of continuing is formidable because of the remote location and depth.

There is a certain feeling of achievement. The goal has been reached. But painfully enough, we have only made it halfway and still have to make it out. Hours of hard work still await us. When Sami and Kai have rested enough, we start heading back. Kitting up in the fine sand is challenging. Sand seems to find its way everywhere, causing O-rings to leak and suit zippers to rattle disturbingly. The shallow and sandy entrance to the second dry passage means that the water is all silted out downstream, as we have struggled our way out of the water and back in again. This proves to be exactly the case. I drag the dry tube behind me, soon realizing something has gone wrong when re-packing the tube. It is vertical instead of horizontal, making the going slow in the small tunnel. I feel my way through zero visibility, feeling exhausted already. Finally, I reach the shore and climb out of the water. The balance of the dry tube needs to be fixed. As if this wasn’t challenging enough already, I realize that my suit is leaking. Even though the holes are only needle size, as I later find out, there is enough water seeping in to soak me.

I’m trying to figure out the best strategy of getting over the dry passage with all the tanks and tubes. At least I don’t have to worry about sweating as I’m totally wet already. Diving out will not be fun. I’ll just have to endure it, that’s all. The first task is to move the rebreathers. Carrying them is otherwise fine, but the last restriction once again means crawling face-down in the water, squeezing between the rocks with the unit in the back. When reaching the other side of the restriction, I am breathing heavily and feeling totally out of energy.

We have a brief discussion. The gear could be left behind for the next day, or it could be hauled out immediately. We decide to carry everything immediately, a decision that I soon regret. The work intervals get shorter and shorter. As your strength dwindles, it becomes harder and harder to find a good step in the streaming water, not to mention climbing over the boulders littering the passage. I keep thinking about the next day. If I can carry all this out, I do not have to return. That gives me just enough strength to get the last cylinders from the sump two.

I find a dry pair of gloves in the dry tube. I know they won’t help long, but they feel heavenly until I submerge again. I immediately feel the cold water starting to make its way towards my fingers and gradually numbing them until they are almost useless.

After we have carried the diving gear through the second dry chamber, Sami and Kai are ready for the push dive. Standing on the narrow strip of sand, we help them kit up and wish them good luck as they disappear into the darkness. It is time to see how far the diveable cave continues.Although there is only a half an hour dive out, it feels like hours. My hands are clumsy. My thinking is slow, and I have to concentrate on every small task. Each time a stage has to be moved it takes a lot longer than usual. I am shivering. Looking at others, it seems I’m not the only one fighting against tiredness. When we get to the final restriction before the chimney-like crack in the stone leading to the surface, we need to organize our gear for the ascent. This usually takes a minute or two, but this time, it seems it takes us fifteen minutes to get through. Everything is happening in slow motion. When we reach the narrow upwards corridor, I shiver from relief. The last obstacle has been cleared, and the cold doesn’t matter anymore.

After more than 12 hours inside the cave, we surface into the night among the fells. The stars greet us, slowly blinking above us as if showing the way home. But I don’t waste any time getting out of the water. Walking along the shore, I feel the water filling my boots. Had the dive been an hour longer I would have been in serious trouble.

And as if we hadn’t had enough to endure, the snowmobile decides not to care about our attempts to start it. After an hour of tweaking, the old engine bows and kicks into life. At least we have transportation back to the car. Even with all the carrying it takes a full hour before I start to feel warm again.

Day 3

The following morning isn’t the most pleasant. My body is still aching from previous day’s efforts. We still need to complete the photogrammetry from the first sump, so I have no choice but to crawl out of bed. Again we assemble and load our rebreathers into the car.

The temperature is still close to zero degrees, but this time, a fierce wind is making the air feel much colder. Being tired and worn out, plus having still damp undergarments add to the chill. My body feels cold, and my sleep-derived mind is slower at making decisions. I have to keep telling myself to keep focused.

Entering the water, we soon discover a bigger problem. The o-ring of the camera housing isn’t in place, and the camera is flooding. So much for the photogrammetry. This is such a typical example of small mistakes that begin to pile up when you become tired and try to get too many things done at the same time. We dive anyway and take a few stills. After fetching the stages left behind the day before we were ready to call it a day – and a project. My suit is still leaking, and I happily turn around once the pictures are taken.

The push dive is over, but there is still hours of carrying, diving and crawling ahead. After some 12 hours inside the cave, we finally surface.Later on, we are sitting in Torsten’s sauna and reflecting on the excitement of the project. In two days, we were able to push to the end of the line and stretch it a bit further. We were moving fast, with the minimum safe amount of equipment. We were able to help the two push divers reach the end of the line. We would not have been as tired had we allowed ourselves a day or two more for the diving. But we wanted to move fast. And I must admit that is all part of the excitement, pushing the limits enough to feel it with every cell in your body.

I am so happy that I am lucky enough to have this possibility. To push on with these determined explorers, always ready to expand the limits.

Underwater photos and videos: Janne Suhonen, Kai Känkänen and Sami Paakkarinen Story: Antti Apunen Surface photos and videos: Thomas Broumand Divers: Antti Apunen, Veli Elomaa, Kai Känkänen, Sami Paakkarinen, Janne Suhonen and Jenni Westerlund

READ MORE

SIGNAL SEEKER – A SHORT STORY ABOUT BO LENANDER'S LIFELONG JOURNEY

Signal Seeker - A Short Story about Bo Lenander's Lifelong Journey

In 1979, Bo “Bosse” Lenander was hiking in the Bjurälven natural reserve. He was enjoying the northern Swedish landscape with its lush green beauty of the summer, making his way along the river running through the limestone valley.

Bosse arrived at the river source. Being a curious individual, he was soon in the water, freediving to the bottom of the pool. There he found a 10-centimeters wide opening, water flowing through it. There was a cave behind.

The Swedish word 'dolin' describes a formation where erosion causes the ground to collapse into a water-filled cave. The cave in Bjurälven Valley originates in the lake Bosse dived, Dolinsjön (Dolin lake), and was therefore given the name Dolinsjö cave.

For many years, Bosse's discovery stayed as a footnote to the Swedish cave exploration. Attempts were made to enter the cave, but the hard flow denied access during the summer months, hurling water out at tremendous speeds up to 20 knots.

Exploring the cave in winter

In 2007, a group of Swedish cave divers decided to make an attempt during the low-flow winter season, even that it meant hauling gear through the deep snow and making a hole in the meter-thick ice. On the other hand, the snow would protect the fragile nature reserve from being damaged by the expedition.

The idea proved right. After transporting the gear through the snow filled valleys and forests, divers managed to dig their way in and map 50 meters of the underwater passage. The cave kept going. So the divers returned every winter, to add a few meters of line and discover what's behind the next corner.

Signal seeker joins Expedition Bjurälven

In 2011, the expedition team invited Bosse to join. A glimmering blanket of snow covered the Bjurälven Valley when he arrived on-site. This time, he decided, there would be no freediving for him.

But Bosse had another idea. As he was an active radiolocation hobbyist, he had built a device that could detect magnetic pulses from underground. These, he figured, could be used to pinpoint the exact location of the divers and features of the cave. This may all sound like an easy task until you consider that the cave is surrounded by a thick sheet of marble and layer of gravel originating from the ice age, blocking most signals from passing.

Bosse's concept proved to be working and is now used by the expedition to record exact locations of the cave formations.

244 hours of diving in a week

The cave was re-mapped during the 2016 expedition. A new generation of precision equipment had become available, and a new map of the cave was soon created, including a full 3-D rendering. Suunto EON Steel compasses were the tool of choice for the underwater mapping. Also, fixed points were placed inside the cave and located on the surface using radiolocation and advanced satellite positioning.

In April 2016, the Expedition Bjurälven team managed to extend the mapped parts of the cave to well over 2 kilometers. They found a massive collapse after sump five, and another sump after that. Longest exploration dives to the end of the line took 7 hours to complete. Divers spent 244 hours in the cave during the expedition week.

Today, 37 years since Bosse's discovery, Dolinsjö cave is one of the longest water-filled caves in Sweden. Bosse is still an active member of the expedition team, regardless of his age of 70.

Well, you know what they say about rolling stones.

The one thing every freediver needs

A dive computer makes freediving safer, more enjoyable and helps to improve performance.

Ute Gessman began freediving before the first dive computers were on the market. The AIDA sport officer and competition freediving judge would instead in those days carry a manometer (a mechanical device for measuring pressure) down with her, which was often inaccurate.

Since then, dive computers have become a must for every freediver, she says.

“For freediving, you need a freediving computer,” she says. “Without one, you have no idea where you are.”

Ute Gessman is competition freediving judge and works for AIDA. © Ute Gessman

Here’s why a dive computer is essential kit.

Safety first

A dive computer can tell you how long you’ve been under the water, your depth, and when you must return to the surface. It also helps your buddy at the surface to keep track of how your dive is going. “I can see when he or she left the surface, how long they’ve been under and when he or she should reach the bottom,” says Suunto’s dive business line manager, and freediver Jyri Vehmaskoski. “A dive computer also tells me when I should go down to do the safety dive, about 10 or 15 m, to make sure they’re okay as they come up.”

Jyri Saarikorpi is a freediver and spearfisherman. © DeeDee Flores

Preparation

“A freediving computer helps you prepare on the surface for a dive,” Ute says. You can use the dive computer to time different breathing exercises, to keep track of your warm up dives, and to tell you when you should commence the dive.”

Suunto D4i Novo is a lightweight dive computer that has four diving modes, including freediving.

Overcoming anxiety

“When most people start freediving, they are a little bit afraid to use the free fall to go down the whole way,” says Ute. “Using a dive computer helps them to relax because it tells you how long you should descend before turning back. “Some people want to work by a time, so they put a dive time in, so they know when two minutes, for example, has passed then they need to go back.”

© Ute Gessman

To manage dive stages